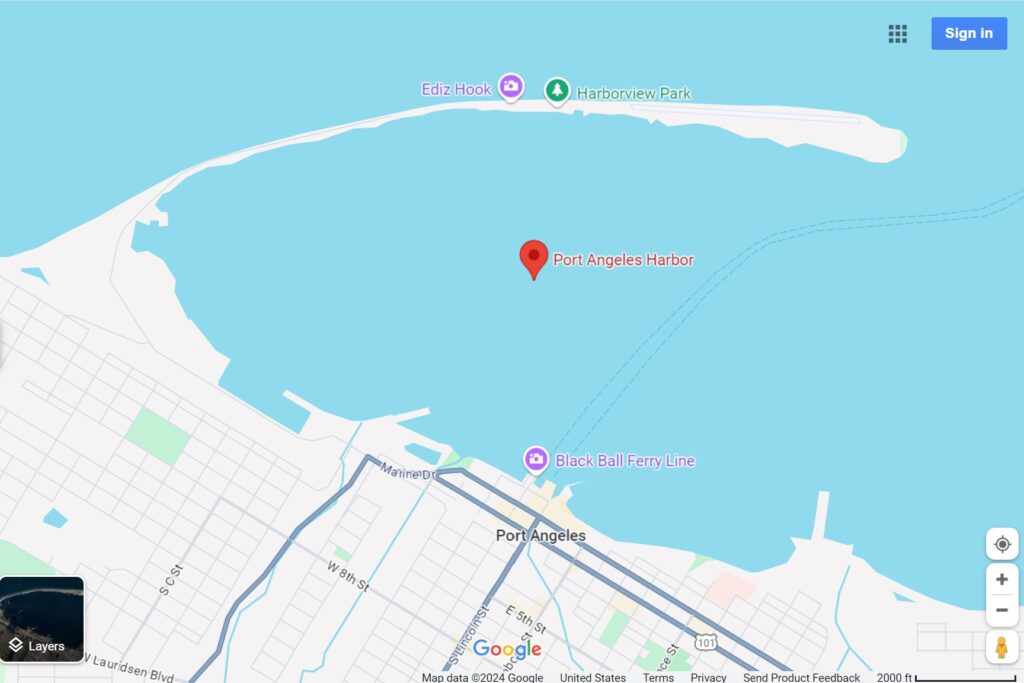

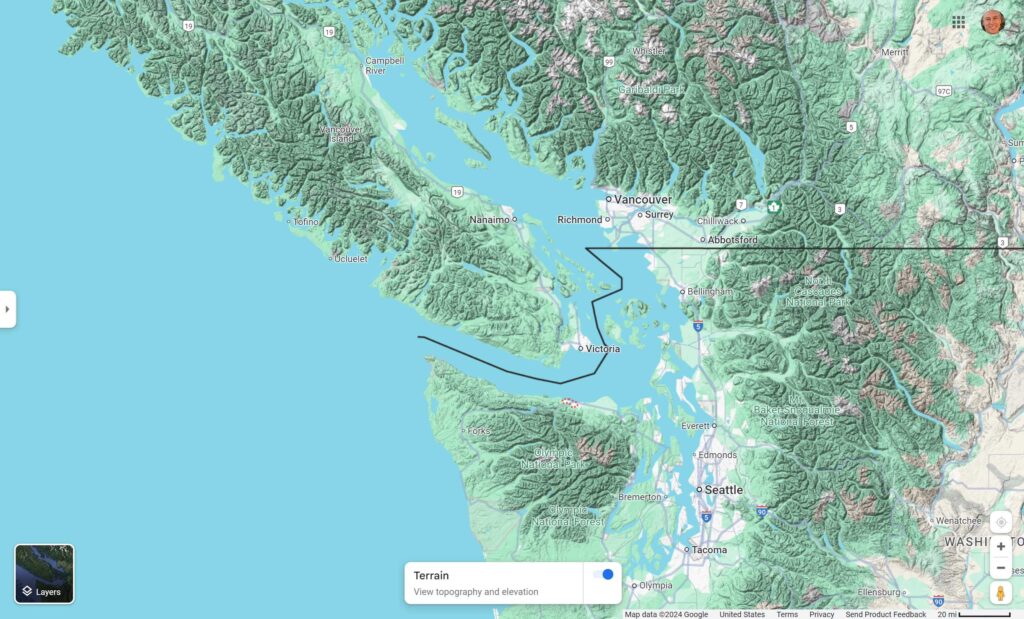

A jellyfish swarm, also known as a bloom, smack or mass aggregation, occurred in Port Angeles Harbor on Friday, November 15, 2024. Several jellyfish species, and similar jelly-like but not jellyfish species called salps, were sighted pouring into the harbor alongside the inner tip of Ediz Hook. Jellyfish are also known as sea jellies. The number of jellies in this smack is unknown, but likely ranged from hundreds of thousands to over a million.

Jellies and salps are both simple and amazing creatures. They appear in large groups and as solitary animals. Jellies only have one body hole (for mouth, anus, and reproduction). Jellies swim and salps have jet propulsion. They navigate. They hunt. Jellies have spring loaded and poison tipped barbed darts. They eat anything that will fit in their hole. They have a unique life cycle and reproduce through multiple methods. They are sensitive to climate change and they have replaced whole fisheries in some parts of the world.

Jelly swarms (blooms, smacks or aggregations)

Jellyfish swarms are increasingly common in the Puget Sound, and have recently been the subject of study by the Washington State Department of Ecology (DOE) in 2014-2015. It’s hard to count the total number so aggregations are measured by “mass category,” which ranges from a mass size of 1 to 5, where 5 is the largest. Mass size tends to be larger in late summer-fall. In November, mass sizes counted have ranged from about 2.2-3.8. A jellyfish smack can “easily exceed hundreds of millions of individual” animals in an individual Puget Sound finger inlet, such as Budd Inlet.

Jelly and other species observed in the PA smack

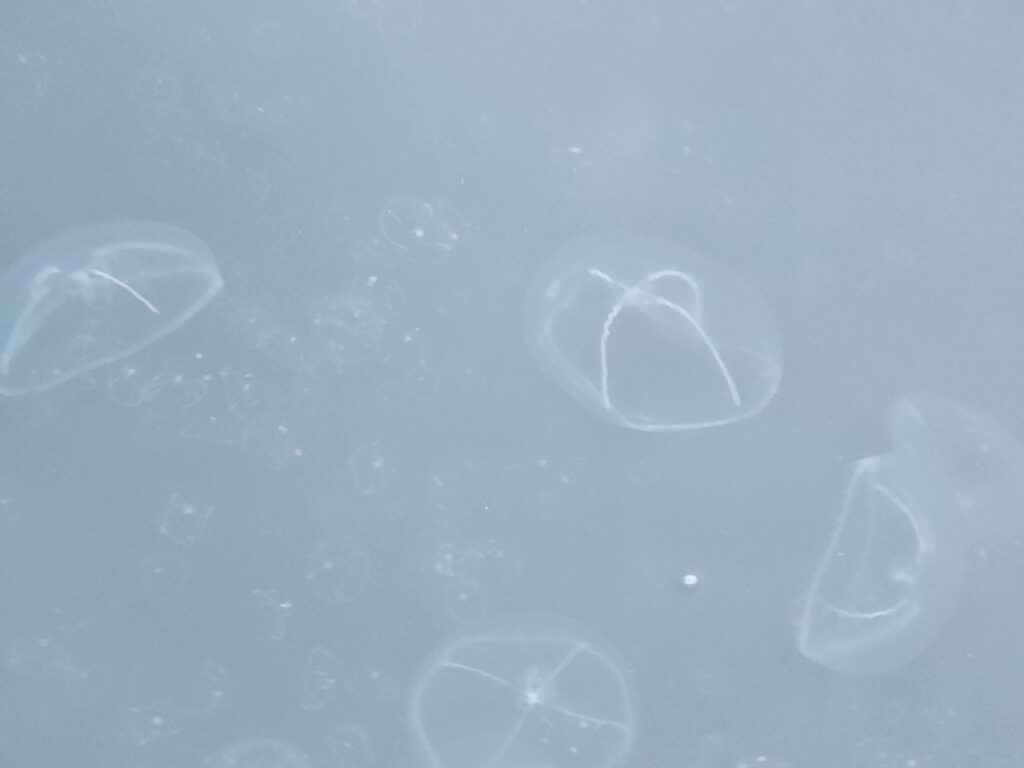

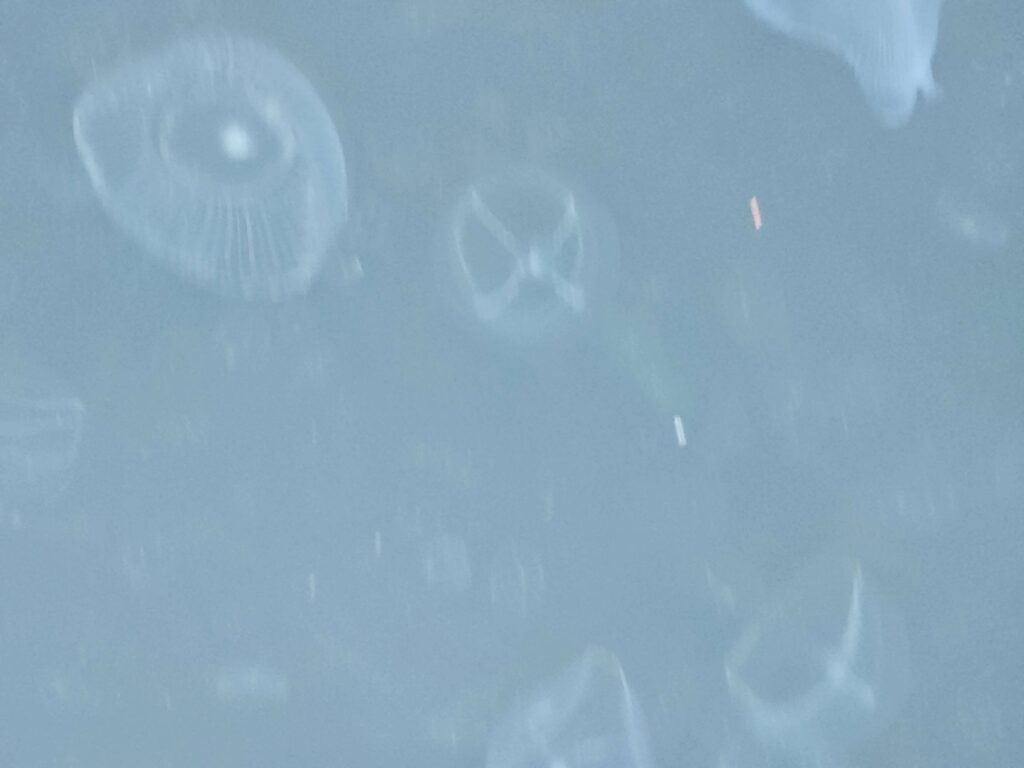

Several observers predominately saw cross jellies, both younger and older adults and juveniles. Also seen were crystal jellies, moon jellies, egg yolk jellies, box jellies, water jellies, and beautiful and stinging pacific sea nettles. Salps and sea lice were also seen.

Some jellies were hard to identify. I don’t know what the string critter is (picture below left), do you? It definitely had propulsion and was able to move against the current in the marina. An observer from New Zealand said they called them sea lice and that they sting as they wrap around you. The Feiro Marine Life Center thought it might be Siphonophore, which is a subgroup of Hydrozoans, which is a subgroup of the Cnidaria phylum. Cnidarian’s includes corals, true jellyfish (Scyphozoa) and Hydrozoans. The critters in the Cnidaria phylum all share in common a decentralized nervous system (no spinal chord) and stingers (described below).

175 species of Siphonophores have been identified. They are not a single critter, but a complex colony of organisms each contributing uniquely to the colony’s survival and reproduction.

There were quite a number of deceased jellies washed up on shore after the morning high tide on Friday, November 15, 2024, such as the moon jelly (below left) with the C-shaped purple sex organs. The crystal jelly’s ridges (below right) under the outer bell are rigid like a washboard.

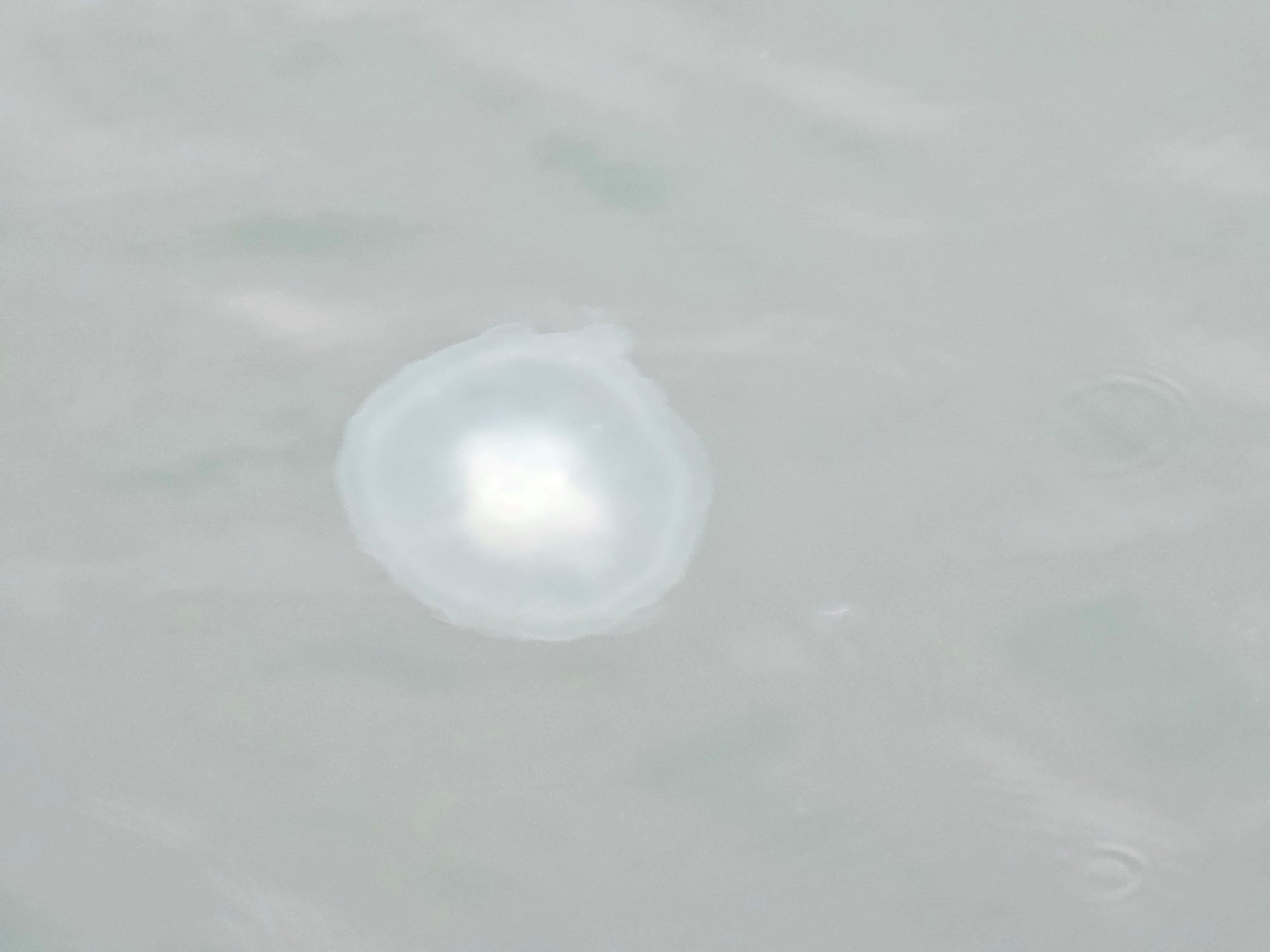

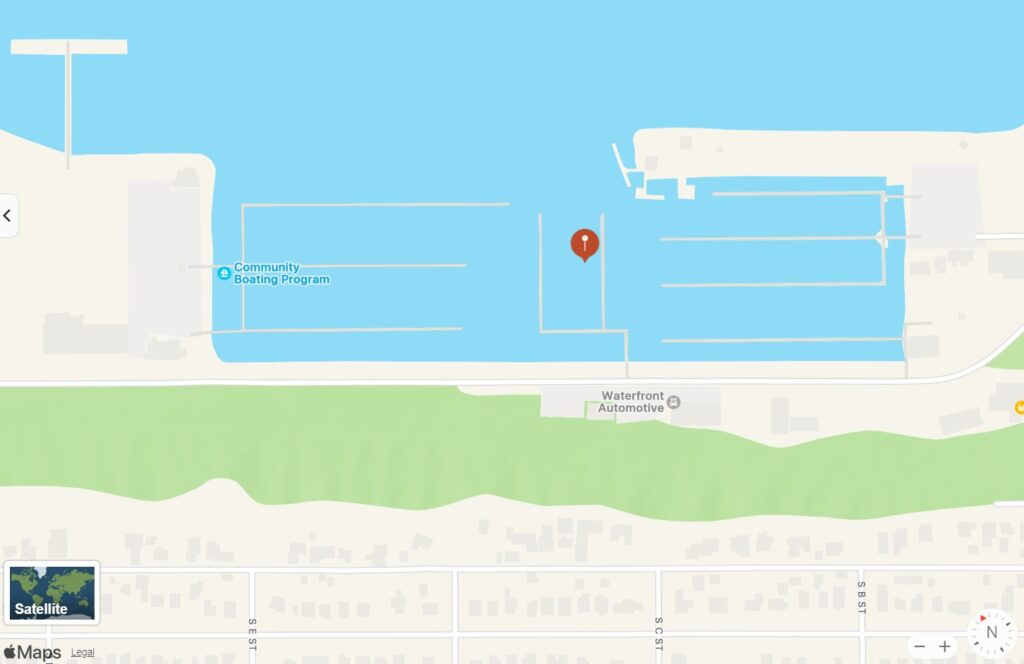

The next day, Saturday, November 16, 2024, a few jellies were seen in all parts of the harbor. They were also seen inside the Port Angeles Boat Haven (marina), but not in mass quantities. One small exception was the collection of crystal jellies in the pictures below. Interestingly, these were hovering at the tail of a freshwater outlet pipe. The water flow from the pipe was substantial, and clear, and the jellies were fighting successfully to stay close to the pipe outlet. But why?

Salps

Salps were seen in abundance in the November 15, 2024 Port Angeles Harbor smack. Salps are not jellyfish and not even related. They have a spinal chord, which makes them related to humans and all vertebrates.

Salps live in two phases. The first is as a single organism (picture above left), and the second is in a colony (picture, above right). Can you see a second single salp in the picture on the left? (Hint, the second yellow dot is part another single salp lower in the water.) According to the Feiro Marine Life Center, the animal on the right is likely a colonial salp of a Cyclosalpa species. Salps are best known in the colony phase. If you search the internet, or read the Wikipedia page for salps, you’ll see lots of pictures of salp colonies. One such picture in the Wikipedia article is a circular ring cluster of pelagic salps in New Zealand, which looks very much like the salp colony in the picture above.

Salps do not have tentacles nor a stinging mechanism. The white filament, or ribbon, is a stolon which only appears on the aggregate-colony form of a salp, and it’s function is to clone babies. They collect and eat phytoplankton with a mucous net inside their jet propulsion tube. You can just barely make out the tube structure in the picture of the single salp, above left. Very small fish can swim into and hide inside the salp tube, effectively cloaking themselves with an invisibility shield. (I’m not sure if that tickles the salp, what do you think?)

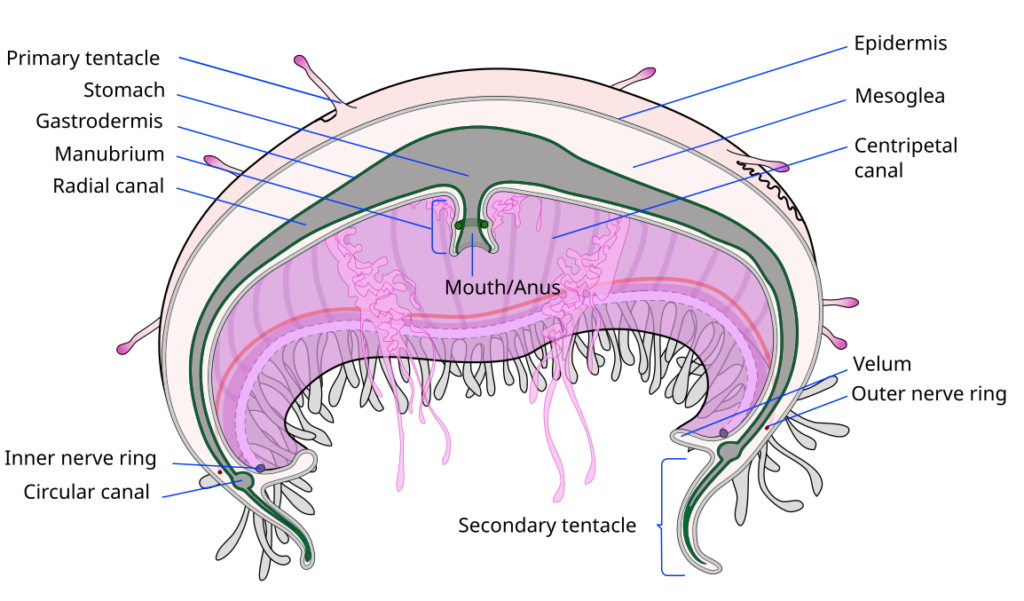

What is a jellyfish?

They are surprisingly interesting animals, both extremely simple and complex. The have no blood, no heart, no lungs, and of course no bones. They have no brain, although they have a nervous system which senses and responds to the environment.

Jellyfish eye

Some species have a more evolved nervous system and a rudimentary eye. In some species the “eye” is very simple and only senses for light. In other species, particularly the box jellies, they have a more evolved structure clearly identifiable as an eye which they use to move toward or away from light and also to navigate around obstacles. Depending on the box jelly species, they have 1-4 eyes, and at least one species has 24 eyes.

One body hole

A jelly has one hole: the mouth is also it’s anus and entry/exit way for the sexual organ. Yes, it eats and poops and delivers and receives sperm and eggs from the same hole.

Some jellyfish facts

There over 2,000 jelly species. The bell height and diameter ranges by species from 0.5 millimeters (1/32 inch) to 2 meters (6.5 feet). Their tentacles can range from 1 inch long to 119 feet long. The lion’s mane jelly is the longest, longer than any whale, and may be the longest animal on the planet. Lion’s mane jellies live in the Salish Sea, although they are not reported as growing that large here.

They can release as many as 45,000 eggs daily.

Their diet is varied and includes plants and animals tiny to small: protozoa, phytoplankton (plant), plankton (animal), zooplankton, rotifers, eggs, crustacean larvae and grown crustaceans, larval fish and small fish, and other jellies. Each species eats different things, but most or all are carnivorous. Some eat whatever attaches to their tentacles and fits in their mouth, so any kind of small creature.

Jellies swim, and navigate

Jellyfish are considered by most as planktonic, in that they float with the currents. But, they are not simply passive creatures subject to the whims of currents, they have the power of locomotion. Typically they move about 1.5 meters (5 feet) per minute, and some can travel up to 4 meters (12 feet) per minute. They can move in any direction including against the current. Some species, like the pacific sea nettle can move up and down the ocean’s water column 1100 meters (3,600 feet) per day. Yes, per day!

Since they never stop swimming, even at a leisurely 1.5 meters per minute, they can travel 2,200 meters (7200 feet, or 1.36 miles) per day. Presumably, that can be extended or offset depending on how they navigate currents and whether or not they choose to stay in one location for a while.

I watched this pacific sea nettle in the gallery below swim around in the Port Angeles Boat Haven on November 16, 2024. I first saw it swim (west) past the wood pier, which was up-current. It then turned 90 degrees and swam to the left (south), bumped into a wooden bulkhead, turned around 180 degrees and swam north past that pier post, and then again west, where it bumped into a cement pier. Despite the current wanting to push it east, it stayed in a very small area for at least 15 minutes.

Two types of tentacles

The long stringy tentacles are the true tentacles and contain all or almost all the stingers. The other kind are called oral arms, which assist with collecting food and bringing it to the mouth inside the bottom of the bell. The oral arms can also hold a brood of baby jellies (called planula). For the pacific sea nettle jelly (above), the red strings growing out sides of the bell are the tentacles and the lighter colored mass that flow from the middle of the bell are the oral arms.

Sometimes the tentacles are hard to see. For many of the cross jellies, pictures above, it was hard to see if they had tentacles. Crystal jellies don’t appear to have tentacles, because they don’t. They aren’t actually jellyfish, although they are closely related. Crystal jellies are in the Hydrozoa class of the Cnidaria phylum, and jellies are in the scyphozoa class of Cnidarians.

Sometimes the tentacles are translucent or fine like a hair, and difficult or impossible to see.

Jellies hunt with poison tipped spearguns

Jellies can sense their prey and move towards it. They hunt!

Jellyfish are voracious hunters. Their vortex-creating swimming action can also draw in food to the tentacles and they never stop swimming or eating.

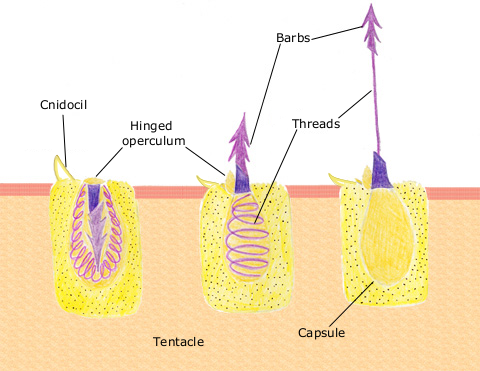

Jelly tentacles have an amazing weapon. Each tentacle is loaded with many, sometimes millions of spring loaded barbed harpoons filled with a neurotoxin. These weapons hide in a tiny cyst cavity just beneath the surfaces of their skin. The lion’s mane jelly can have 1,200 tentacles, some up to 119 feet long, covered in cysts containing the barbed hooks. These weapons are scientifically called cnidocytes.

Jellyfish are in the Cnidaria family (the C is silent, it’s pronounced ny-dar-ee-uh), which includes jellies, corals, anemones and hydroids (tube forming polyps with tentacles). All species in the cnidaria family have these attack cells, although the level of toxin varies by species. This attack cell, has a small hair like structure on the outside that is triggered by contact or chemical presence. Inside the cell there is a chemical which facilitates water rushing quickly in once triggered, and the cell “door” opens and water jets back out carrying the barbed hook. The cell is triggered and the barb is released in a split second with an explosive amount of pressure.

Different members of the cnidaria family have different types of attack tools, which may not have a barb at the end of the attack string. Instead, the launched string can either wrap around the prey, or stick to it. Some anemones, like the starlet sea anemone on the U.S. east coast, has all three kinds of attack methods. The sticky-Velcro feeling you get when put your finger in a Salish Sea anemone may be from the sticky attack strings, or from barbs ripping off the top layer of your skin.

Cnidarians, including jellyfish, have the intelligence to know if something they touch is potentially prey or not, which is why they don’t sting themselves. Although they can’t tell if a human is prey or not, which is why they sting us.

Most Cnidarians in the Salish Sea have very mild poison in their barbs. When these creatures don’t need to eat larger prey, they don’t need strong poison. According to the Feiro Marine Life Center in Port Angeles, moon jellies toxic sting is so mild humans don’t notice it, unless their skin is sensitive or they are allergic.

Lion’s mane and pacific sea nettle, Salish Sea jellies, carry enough neurotoxins to cause pain, but not death, to humans.

The Portuguese man o’ war is renowned for it’s painful sting (although it’s not technically a jellyfish, it’s a hydrozoan, like the string critter above), but the Australian box jelly is the most deadly jelly. It’s one of the most poisonous creatures on earth and can kill a human in a matter of minutes if medical help isn’t received. It’s poison was analyzed to include an amazing cocktail of 170 toxic proteins. (The application of diluted vinegar can ease the pain from the stings of some jellies, including the Australian box jelly. Some Australian beaches stock emergency beach kiosks with vinegar.)

Some fish are immune to the poison of some jellyfish, and they’ll swim around and within the tentacles and oral arms for protection. (Some fish do the same with corals, which are in the same family tree as jellies.) Sea turtles, which each jellies, are immune to the barbs because of their armor which is made of the same material as our fingernails, keratin.

Jelly fish are hunted, a little bit

It can be hard for scientists to determine which animals eat jellies because even if they look in their stomachs for what they ate it’s hard to identify jellies from all the other goo in the stomach. A few animals are known to eat jellyfish, including sea turtles, sunfish, sea cucumbers, crabs, shrimp, seagulls, penguins, sea lions and seals. Some jellies are considered a delicacy by some humans.

Jellies are 96% water so they are not a calorie-dense food. However, the inner parts like the stomach pouch, sexual organs and tentacles are nutrient rich so predators often target these parts. Unless immune to the poisonous barbs, an effective strategy is to eat the innards from the top, through the bell material. In the Port Angeles Harbor swarm I saw a number of dead jellies with parts or the middle of their bell missing.

Some websites claim that salmon will eat jellyfish. However, in one incident in Ireland a smack of poisonous jellies were swept into salmon farming pens and quickly killed all the salmon. (See the David Suzuki video referenced below for video footage.)

Unique life cycle of a jellyfish

Jessica Schaub, a PhD candidate in oceanography at the University of British Columbia, researches jellyfish, and the moon jelly in particular.

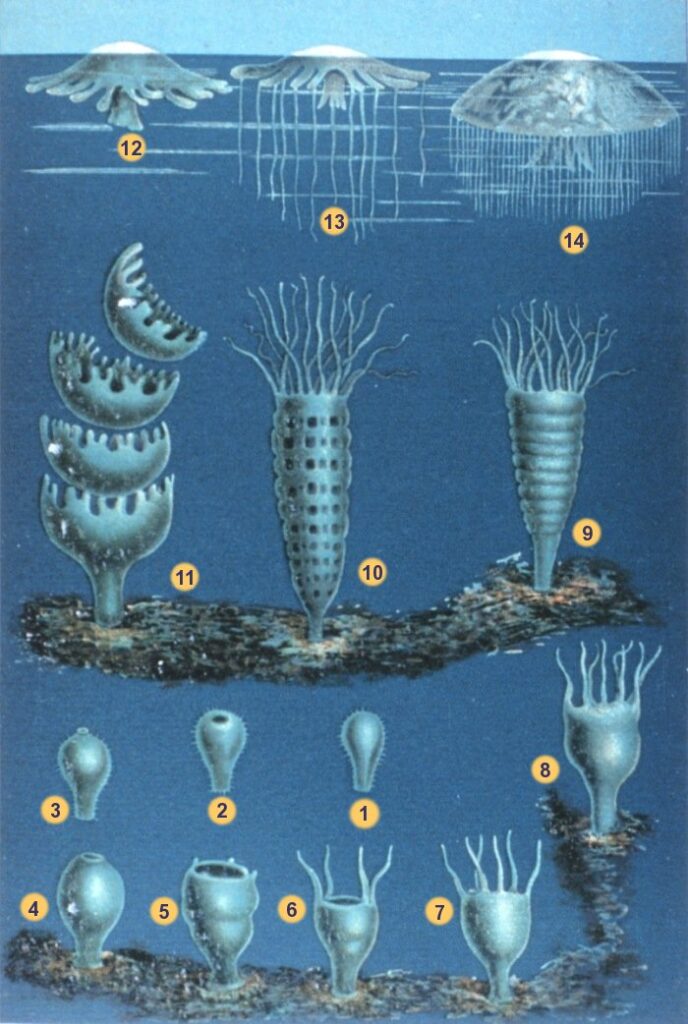

She describes how moon jellies start as a planula larva, a tiny critter .2 millimeters in size, with 8 tentacles. They are so small their growth and eating behavior can only be studied under a microscope. The planula are raised on the underside of the bell or within the oral arms. Eventually they release from their mother and swim around until they find something to attach to, which is usually a rock and can be the underwater portion of a dock structure. The larva grows into a small polyp which lives for many years in a colony.

When the polyps get old enough, they start shedding new jellies, about 10 per year for moon jellies. That process is sort of like growing a flower which eventually wiggles off the main stem. The polyp is cloning itself.

The little clone is a baby jelly, about the size of a quarter (2.5 centimeters, or 1 inch in diameter) called an ephyra. The ephyra grows into a full size jellyfish in about 2 months, super fast. The adult is scientifically called a medusa, because of the bell-shaped body with tentacles.

Jessica considers the polyp to be the main animal. The medusa’s purpose is to mate and produce more larva. The medusa usually dies shortly after producing babies, but the polyp lives on for years, creating new clones.

Jessica describes in her video the amazing process of how the polyp can also clone itself two other ways. The polyp can create a whole new polyp. Also, it can deposit a podocyst which is a seed like critter that can attach to a surface to grow into a new polyp. Podocysts can hibernate if growing conditions are not favorable. As if that’s not enough, the polyp itself moves around. As it “walks” along the thing it’s living on it deposits a podocyst, and those are often found in a line that tracks the polyp’s movement.

Polyps can attach to rocks, but also plastic, wood, common dock building materials. Human activity thus creates more living environments for jellyfish communities.

So if I understand this right, a polyp reproduces three ways. It can make little podocyst’s which can make a new polyp, it can make a whole new polyp, and when it sheds an ephyra it’s basically making a clone of itself whose primary job is to eat, grow, sexually reproduce new babies from sperm and eggs, and then die. Wow.

Jessica’s YouTube video on her research is at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAvTd4Lf1Ik.

Jellyfish and climate change

Jelly smacks are common in the summer, and may be increasing in Puget sound. There is enough concern that the Washington State Department of Ecology conducted a study published in 2016. They are increasing in some parts of the world, sometimes with severe economic and environmental impact.

The Nature of Things documentary on jellyfish by David Suzuki provides a nice overview of their complex nature and harm to world fisheries.

Jellyfish appear to be capable of quickly and massively colonizing regions that are damaged from overfishing or suffering environments detrimental for fish. Fish and jellies compete for resources. In places where jellies have taken over it is hard for fisheries to re-establish themselves.

Preventing jellyfish from overtaking a distressed ecosystem has proven hard to accomplish, so keeping fishery environments healthy is important.

World Jellyfish Day

November 3rd is World Jellyfish Day. Thus, the November 15 2024 Port Angeles smack missed celebrating in Port Angeles by 12 days. If they travel about a mile a day, maybe they celebrated at Salt Creek?

A quick technical note

When I use the word jellyfish and describe a unique feature of the animal I am specifically referencing true jellies which are in the scientific class Scyphozoa. Not everything that applies to jellyfish described above applies to other cnidarians like anemones and hydrozoas. For example, crystal jellies are not true jellyfish, they are in the hydrozoan class and as such don’t have oral arms. Like everything else in the cosmos, there’s always exceptions even for the true jellies and I haven’t gotten into that level of detail here.

Video resources for more information about jellyfish

How does a jellyfish sting? A TED-Ed talk, 4:17 minutes

Jellyfish predate dinosaurs. How have they survived so long? A TED-Ed talk, 5:26 minutes

The one thing stopping jellyfish from taking over. A TED-Ed talk, 5:35 minutes

15 incredible jellyfish species. 18:31 minutes

Vicious beauties – The secret world of jellyfish. Nature, 44:04 minutes

Jellyfish rule. The Nature of Things, David Suzuki, 44:44 minutes

Reading resources

Wikipedia, Jellyfish, overview article

Wikipedia, Cnidaria (pronounced ny-dar-eea), article describing the related group of jellies, corals, anemones and hydrazoids

Wikipedia, Cnidocyte, article describing the stinging cell

Colin, Sean P., John H. Costello, and Eric Klos. “In situ swimming and feeding behavior of eight co-occurring hydromedusae.” Marine Ecology Progress Series 253 (2003): 305-309.

Berwald, Juli. Spineless: the science of jellyfish and the art of growing a backbone. Penguin, 2017.

Gershwin, Lisa-Ann. Stung!: On jellyfish blooms and the future of the ocean. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

I hope you enjoyed this story of another set of amazing and elusive creatures on the Olympic Peninsula and it’s waters. If you have some pictures of the Port Angeles smack and want to share them in this article, contact us at the link above.

I thank the guys down at the Port Angeles Boat Haven Harbormasters office, the couple from New Zealand (via Canada) who shared the joy on the boat launch dock, and photographer and writer (and Port Angeles Farmer’s Market vendor) Nirvan Hope who first spotted the smack at sunrise on Ediz Hook.

I give a special thanks to Tamara Galvan of the Feiro Marine Life Center in Port Angeles for scientific feedback on the article, species identification and reading materials. And also to Jessica Schaub for feedback and clarification on the jellyfish life cycle, for help with species identification and reading materials. Jessica is a PhD Candidate in Oceanography, Pelagic Ecosystems Laboratory, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF), University of British Columbia. Her work is excellent and I wish her all the best in a long career in oceanography.

I spoke to one local sport fisherman who said he caught an unusual amount of jellyfish in his lines last year, 2023. If you have any similar experience, noticing either an increase or decrease, please let us know, or contact the Feiro Marine Life Center.

This article is part of a ClallamCountyBar.com series for families and children on nature on the Olympic Peninsula. Please consider contributing to the series.

Mark Baumann